CCCP.

Four letters that defined an era and became one of the most recognisable symbols of the Cold War. If Coca-Cola was the icon of capitalism, ‘CCCP’ was the shorthand in Western minds for the world they imagined on the other side of the Iron Curtain – a repressive, menacing world driven by ideology and backed by a nuclear arsenal.

If these four letters seemed impossibly rich with dark associations for Westerners, they were supposed to represent only one thing to Soviet Citizens: the glorious Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Soiuz Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik).

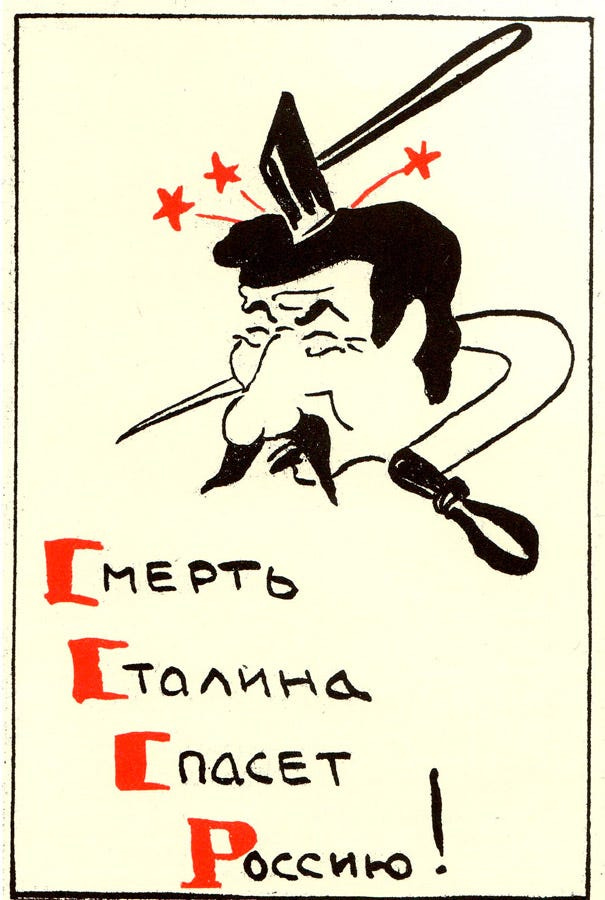

But ordinary Soviet citizens had other ideas, and they set about reinterpreting this and the countless other bureaucratic acronyms and abbreviations that coated Soviet life like alphabet soup. In their hands, ‘CCCP’ (‘SSSR’ in Russian) became:

‘Stalin’s Death will Save Russia!’ (Smert’ Stalina Spaset Rossiiu)

Humour is often at its best when it feels edgy, so the incredible risk of sharing this subversive message made it all the funnier, and the urge to repeat it irresistible to many.

This blistering indictment of Stalin’s leadership became so common that children were reported for scribbling it on their notebooks at school. They were often too young to appreciate the stakes – they just giggled in the knowledge they were breaking some kind of taboo. Still, if the children were only sent to the headteacher’s office, their parents might soon find themselves in the crosshairs of the secret police (the NKVD).

On 25 November 1938, a certain V. Bazhenov, a loyal Party member, took the train from Moscow to Kharkiv, Ukraine. As he walked through the wagons to find his place, he discovered a number of homemade flyers had been jammed hastily into the window frames. There it was again — on sheets of rough green paper, ‘STALIN’S Death will Save Russia’, with an added commentary condemning the leader and his entourage as ‘the true enemies of the people’ who ‘deserve only one thing — death’!

Horrified, Bazhenov rushed to report this outrage to the local NKVD, who promptly launched an investigation. The culprit escaped detection this time, but he or she wasn’t the only one who tried to spread this scandalous material across the country.

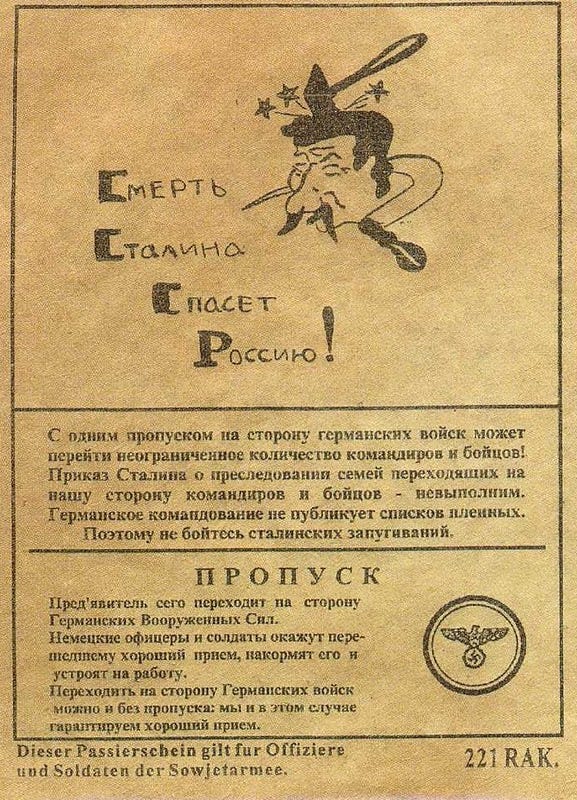

Enter the Nazis

In June 1941, Hitler’s troops invaded the Soviet Union and began distributing a leaflet which carried the same slogan: ‘Stalin’s Death will Save Russia!’, it proclaimed, and went on to provide a tear-off voucher guaranteeing safe passage for any Red Army soldier wishing to defect.

For the Nazis, this slogan was clearly a propaganda tool as blunt as the hammer smacking Stalin on the head. It was designed to attack the Soviet regime – nothing more, and nothing less. But the story inside the Soviet Union wasn’t so straightforward.

Working in the former Soviet archives, I came across dozens of further examples of ordinary people deciphering official acronyms to voice their feelings, and I began to realise that something more important was going on than just throwing a few jabs at the government and its ideology.

For ordinary Soviet citizens living in Stalin’s 1930s, everything they knew was being turned upside-down. In the smoke and steam of massive, badly-managed and frantically-paced industrialisation, people simply didn’t know how to make sense of the chaos.

The newspapers were crammed with fantastic stories of economic abundance, heroic feats, and massive construction projects. But newspaper headlines didn’t touch ordinary people’s lives; it was like reading dispatches from another planet.

Daily life felt anything but heroic and abundant: most people worked themselves to the bone trying to fulfil impossible production targets; they queued for hours each day to receive meagre rations; and when they finally went home at days’s end, they were lucky if their family had more than a corner in a crowded room to call their own.

As a result, even firm believers in the Soviet project struggled to connect the soaring official rhetoric with painful everyday realities. As a loyal worker in Leningrad pointed out at a meeting, ‘these great deeds of ours need to be decoded to reveal [their] great economic and political meaning […] we cannot understand them ourselves without help.’

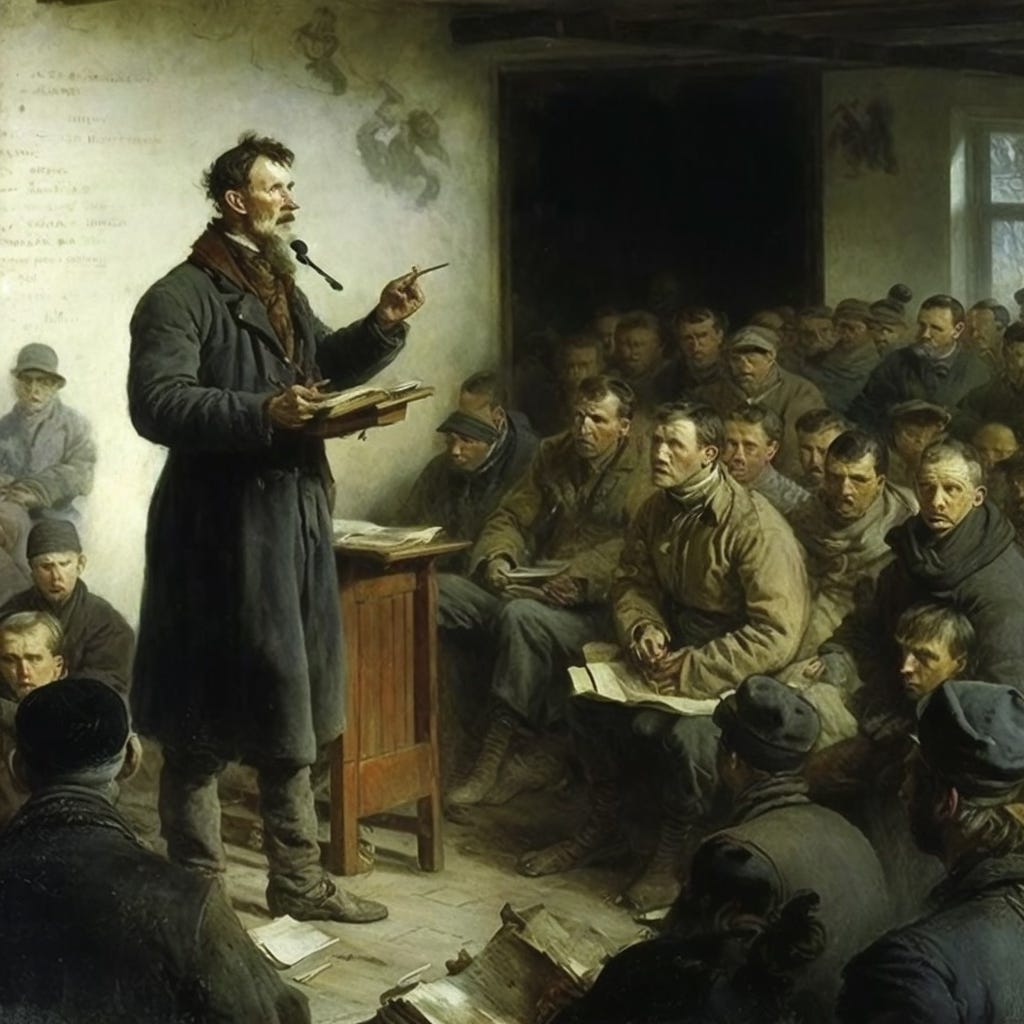

Remarkably, the regime actually agreed with him! An army of ‘political instructors’ was dispatched to the factory floor to work as the regime’s prophets. In lectures, discussion groups and evening classes, it was their job to ‘decode’ the good word of Marx, Lenin and Stalin, to explain that the people’s suffering was all in service to something far greater. They were all, the official narrative promised, building a true utopia on Earth.

Many were convinced, but countless others resisted conversion and instead set about becoming codebreakers: never taking things at face value, reading between the lines, and finding their own ways to decode the confusing world around them.

They fashioned homemade code-keys, breaking down official words and symbols until they reflected the harsh truth of Soviet life as they experienced it. ‘CCCP’ was only the tip of the iceberg.

Breaking the Code

If the newspapers hailed the collectivisation of agriculture as a vital pillar of the new, centrally-planned economy, ordinary people knew that by 1933 it had already caused a famine that claimed millions of lives.

‘MTS’ officially stood for Machine-Tractor Station, the state enterprise responsible for the revolutionary new machinery on the starving collective farms. In the wake of the famine, Soviet citizens hoped for one more victim, making MTS:

‘Comrade Stalin’s Grave’ (Mogila Tovarishcha Stalina)

Even if you weren’t starving in the 1930s, you were likely going hungry. Unless, of course, you were a Party official or a visiting foreigner and had access to the specially-stocked ‘Torgsin’ stores, where payment was in gold, dollars or other hard currencies. ‘Torgsin’ was an abbreviation that officially meant ‘Trade with Foreigners’ (torgovlia s inostrantsami), but it was also decoded letter-by-letter to highlight the devastating economic hardships this unequal system created:

‘Comrades, wake up! The workers are dying — Stalin is destroying the people!’ (Tovarishchi Opomnites’! Rabochie Gibnut’ — Stalin Istrebliaet Narod)

When Nikolai Koniaev, a young student in Kyiv, reeled this out in his college dormitory, he was arrested and condemned to 6 years imprisonment.

Others were more circumspect. In addition to the Torgsin stores, the authorities also tried raising funds by forcing ordinary workers to purchase government bonds – prompting citizens to fold the paper bonds so that the word ‘state’ (gosudarstvennyi) was shortened to ‘shitty’ (govennyi), revealing the true value of the ‘investment’.

Breaking the code was also to break the law in the Soviet Union but, surprisingly, even the secret police wasn’t safe from this kind of mockery.

‘NKVD’ officially meant ‘People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs’, but the codebreakers thought a better description of what Stalin’s faithful bloodhounds stood for was:

‘You might never go home’ (Neizvestno Kogda Vernesh’sia Domoi)

Or:

‘Beat. Smash. Drop. Trample.’ (Naddai. Krushi. Vali. Davi.)

The regime punished these word-games harshly: if a culprit was discovered, they were arrested for ‘anti-Soviet agitation’ and often sentenced to 10 years in a Gulag labour camp. For a single joke, you could be torn from your family and sent thousands of miles away to be slowly worked to death.

Worth the Risk

The risks were immense, but the rewards were often too powerful — and too human — to resist. With the threat of denunciation hanging thickly in the air, honest humour became the gold standard of trust and intimacy.

These homemade code-keys provided more than a brief chuckle ; because it was so dangerous, daring to share them nurtured deep friendships and loyalties. Just a handful of letters, plucked from elements of everyday life, allowed people to voice their real opinions and to sum up so much about their incredibly difficult lives.

In time, these secret codes became a shadow language of in-jokes that quietly but consistently subverted the regime’s obsessive demand for total conformity.

To live surrounded by lies and half-truths is almost intolerable. In small, clandestine trust groups, ordinary people exhorted each other to ‘wake up!’ and acknowledge the elephant in the room. By shooting the breeze and telling jokes, they were proving to themselves that they were not blind, ignorant or brainwashed. They were defiantly telling the truth as they saw it and, in the process, making a powerful declaration: ‘I joke, therefore I am — I can see, I am aware, and I can think’.

Find out more about the hidden world of joke-telling (and its costs) under Stalin in my book, It’s Only a Joke, Comrade! Humour, Trust and Everyday Life under Stalin.