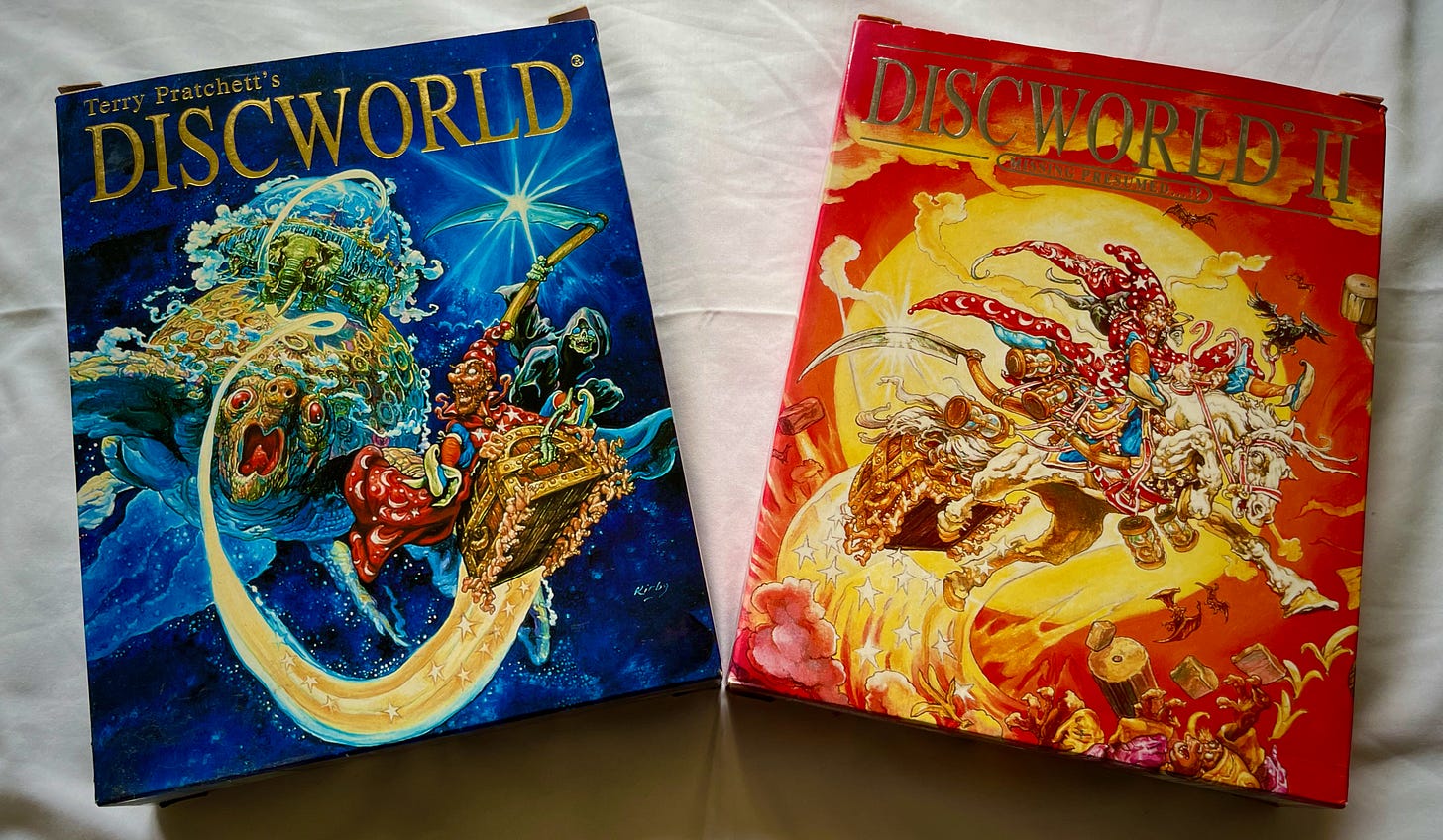

Opening my dogeared copy of Guards! Guards! immediately unleashed a flood of memories. After I first read the physical book, I soon borrowed the audiobook (an actual ‘book-on-tape’!) from my local library, wearing the cassettes thin as I listened to it over and over again. Some of the memories appeared in large, brightly-coloured pixels: portions of the plot were remixed into the first Discworld videogame, released in 1995. A fiendishly difficult point-and-click adventure, I spent months of happy frustration trying to complete it with my Dad on our classic 486 Pentium computer. Dad worked very hard back then, usually coming home late, so those hours working together to solve puzzles and laughing at the gags were always precious to me (and yes, we definitely needed the walkthrough).1

Guards! Guards! is the Discworld novel I’ve most often recommended or gifted to people who’re considering dipping a toe into Pratchett’s world. Although not as complex as later instalments of the City Watch sub-series, it marked a noticeable step up in quality – there’s a greater depth to both the plot and to the major characters. Its Noir detective flavour also brought a grittier sense of reality and moral ambiguity to the Discworld, qualities that increasingly evolved Pratchett’s work beyond simple satires of the Fantasy genre.

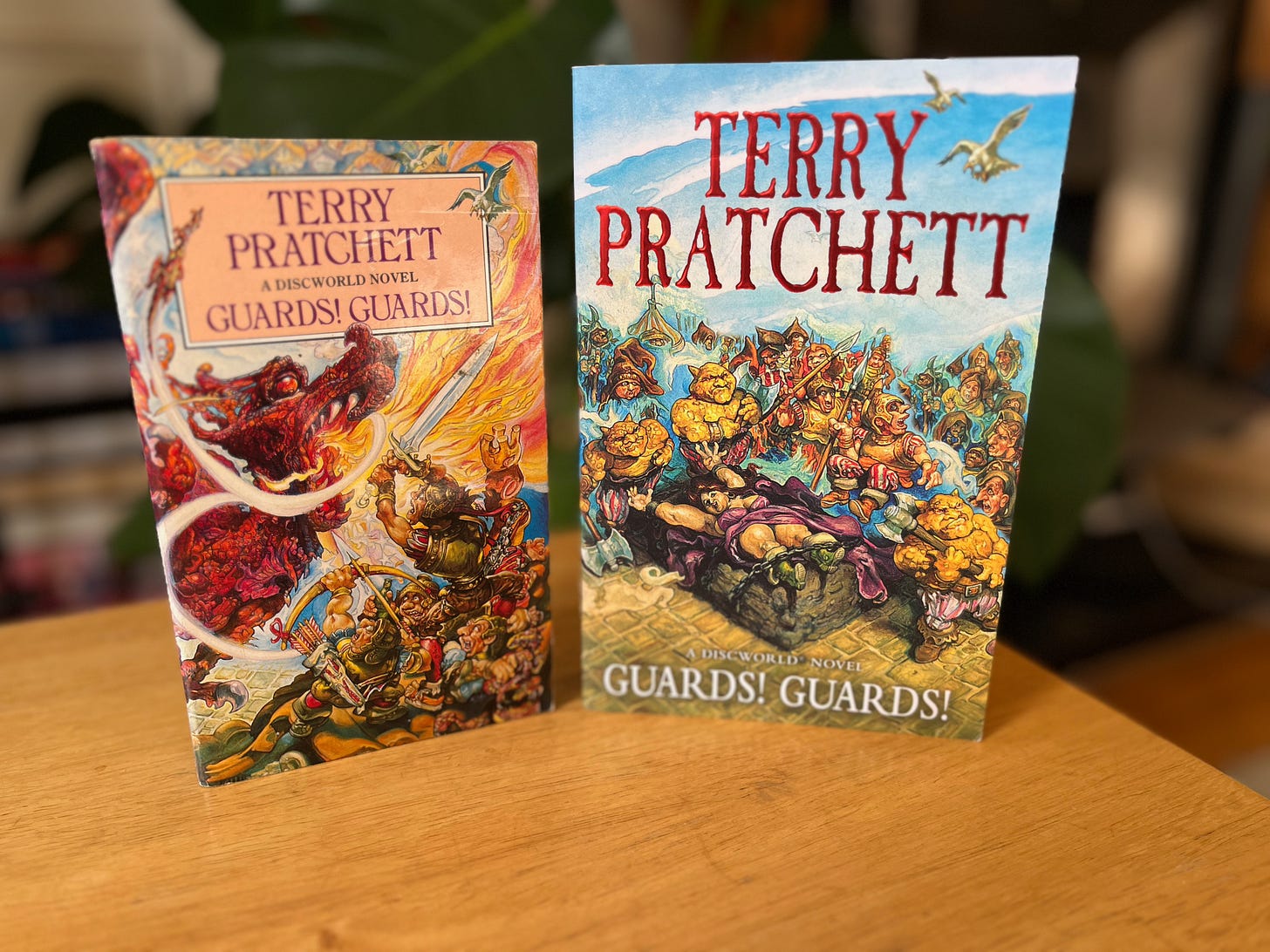

Strangely, it doesn’t seem like the publisher noticed or wanted to highlight this shift. The back cover of my 1996 paperback screams in all-caps that ‘AFTER THIS, DRAGONS WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!’ – a message as incoherent as it is unrelated to the plot. No, after this, it’s Discworld itself that would never be the same again. It would be more complex, more interesting, and driven by a desire to expose and explore the foibles of humanity itself.

To be fair, the deeper themes of Guards! Guards! went over my head, too, when I first read it as a young teenager. After dumping my school rucksack in the corner of my bedroom, I’d grab my copy from the bedside table and lose myself in the jokes and the fantasy for as long as I could before dinner. But this time, beyond the pleasant waves of nostalgia, the novel revealed much deeper and darker ideas than I could grasp back then. Beneath the surface, this is a book about selfishness, social exclusion, and the banality of evil.

Love Letter

As the dedication makes clear, this book is a love letter to the faceless men whose ‘purpose in any work of heroic fantasy’ is ‘to rush into the room, attack the hero one at a time, and be slaughtered. No one ever asks them if they wanted to’. The people, in short, who respond to the cry of ‘Guards! Guards!’.

Whether it’s movies, books or videogames, their role is little more than ‘cannon fodder’ or ‘unthinking goons’. We can imagine that Guards! Guards! was born from Pratchett asking himself ‘who are these poor sods?’, and ‘what would it really mean to be a guard, a watchman, a policeman?’ – and then writing a novel to find out. The answer we get certainly isn’t pretty or romantic. To be more than an NPC in life is incredibly demanding. It means making difficult choices: whether to follow bad orders; to choose between easy selfishness or putting your backside on the line; and whether to genuinely care about what is right, rather than finding excuses to justify a quiet life of small but endless moral compromises.

A dragon is terrorising Ankh-Morpork, largest and most iniquitous city on the Discworld. Summoned by a secret cabal of disgruntled losers calling themselves the Elucidated Brethren of the Ebon Night, the dragon is supposed to unleash a brief reign of terror. The conspirators want to cow the city into accepting a puppet king so that they can finally act out their fantasies of power. In other words, their plan is to stage a ‘false flag’ operation: they summon a dragon, then provide a likely lad with a shiny sword to save the day. Knowing how these fairytales are supposed to play out, the Brethren expect the city’s population to immediately crown their saviour as the long-lost king of Ankh-Morpork. But the plan goes wrong; very wrong. The dragon proves uncontrollable and takes the throne for itself.

The new dragon-king is every bit as cruel and monstrous as we would expect. It terrorises the city and forces the Brethren’s leader – Lupine Wonse – to be its emissary to the city’s bigwigs. The traditionally-minded dragon demands a regular human sacrifice of an eligible maiden as tribute, and although the citizens are at first appalled, soon enough they’re finding plenty of excuses to accept the new status quo.

The only ones willing to stand against this tyranny are an unlikely band of misfits: the dregs of Ankh-Morpork’s city guard, led by the alcoholic Captain Vimes. Energised by a new recruit – the naïve and literal-minded Carrot Ironfoundersson – the Watch have to overcome a lifetime’s worth of fear and apathy to stand against not only the dragon, but the far more dangerous force of most people’s willingness to accept evil and injustice.

The rise of the City Watch, and of Captain Sam Vimes in particular, forms an arc across the Discworld series. In time, the sub-series would provide a setting for Pratchett to tell detective stories that explore tense and challenging themes, from war and slavery to racism and revolution. But it begins – quite literally – in the gutter, with drunken Captain Vimes mumbling a noir-movie pastiche in which he pictures the city as a femme fatale who’ll break your damn heart, no matter how much you love her. Here, in book one, the City Watch is merely (in the words of Ankh-Morpork’s Patrician), ‘a bunch of incompetents commanded by a drunkard.’ He’s absolutely right, but, more importantly, he’s designed it this way: ‘It’s taken me years to achieve it. The last thing we need to concern ourselves with is the Watch’.2

Over the years, the Watch has simply rusted into the background. The guards themselves don’t really know what they’re for – they steer clear of dangerous streets; chasing criminals is more trouble than it’s worth; and, in any case, the powerful Guilds are the only real ‘law’ in the city.3 It’s not a pretty picture, and for long-time Discworld fans, it’s jarring. One of the strangest aspects of re-reading a long series is how the earlier instalments feel both familiar and alien at the same time. Like Ankh-Morpork itself, I realised that my sense of the Discworld had built up gradually, layer-upon-layer. I’d got used to seeing only the most recent levels, half-forgetting the basements, abandoned passageways, and the rough foundation stones on which everything new rests.

Law & Order

Re-reading the book I was repeatedly struck by how deftly Pratchett breathes life into his characters and their world. Guards! Guards! was a turning point for the Discworld’s most famous (and most pungent) city. Until this book, Ankh-Morpork wasn’t much more than a thumbnail sketch; we had a general sense of the place, but little understanding of the details, of how it actually worked. In this novel, the city comes surging forward into three-dimensional life.

Unlike so many Sci-Fi and Fantasy world-builders, Pratchett doesn’t spend pages (and rarely even a paragraph) lecturing us about the rules and realities of his creation. Instead, we absorb it by listening to what the characters say and following them as they navigate this strange world. The veteran watchmen were born, raised and damaged by this city; combining their jaded perspective with new recruit Carrot’s naïveté is the perfect means for Pratchett to reveal the people, streets and culture of the city through eyes both old and new.

Under its Patrician, Lord Vetinari, ‘for the first time in a thousand years, Ankh-Morpork operated’, but it’s still a far more dangerous place than it becomes in later books.4 At this time, as Vetinari himself notes, the city is wobbling along ‘like a gyroscope on the edge of a catastrophe curve’.5 It’s a city for very cautious people because, when you’re in it, you’re either cautious or you’re dead.

In Vetinari’s Ankh-Morpork, there may be a certain kind of order, but there is scarcely any law. Which is why the Watch – the supposed guardians of the law – will eventually become so important in transforming the Discworld’s largest city from a medieval nightmare into something approaching a modern liberal society.

Still, this is no simple tale of ‘progress’. Pratchett never believed in quick fixes or easy answers. As a satirist, he dedicated himself to exposing humanity’s contradictions and self-deceptions, to exploring the often vast (and hilarious) disconnect between how things are supposed to be, and what they really are.

This is brought vividly to life in Carrot’s bumbling attempts to apply the letter of the law to a far messier reality. He struts into the chaotic city, clutching a copy of the Laws and Ordinances of the Cities of Ankh and Morpork, a compendium of largely-forgotten legislation that has as much relevance to contemporary life as a chocolate teapot. The only time this tome comes in useful is when the literal-minded Carrot is ordered to ‘throw the book at him’, knocking the Brethren’s sinister leader off a precipice. In this book, the law is only effective – and order is only restored – when it’s applied in a thoroughly pragmatic and direct way. Although it can certainly be used as a weapon, Guards! Guards! frequently reminds us that the Law is more important than mere Order. Somewhere between the letter of the law and outright tyranny lies the possibility of something better – something which provides both stability and the flexibility that humanity needs in order to live and work together.

Fantasy & Reality

One of Pratchett’s signature moves was, as his assistant and biographer Rob Wilkins puts it, to take ‘received and dusty storytelling formalities’, the clichés and tropes we’ve seen a thousand times before, and then perk‘them up by instantly undermining them’.6 In the process, everything suddenly tastes fresh and feels so much more real, inviting us to discover something important about ourselves within his fictional universe.

Within the first few pages, Guards! Guards! provides a perfect example: the long exchange of esoteric passwords needed to gain access to the secret meeting place of the Elucidated Brethren (‘the significant owl hoots in the night’, or ‘the cagèd whale knows nothing of the mighty deeps’) is the stuff of countless classic films and fantasy stories. We know how this is meant to go; we know about Masonic Lodges and secret plots: it’s obvious what’s going on. And that’s why it trips us up when it turns out that the cowled figure has actually knocked on the wrong door, and that he’s almost gained access to a completely different secret society because its clichéd passwords are nearly identical. And then, when our lost conspirator does make it to the right address, the doorkeeper has to ask, ‘Would you mind giving it a push? The Door of Knowledge Through Which the Untutored May Not Pass sticks something wicked in the damp’.7

Like so much of Pratchett’s work, it’s not just funny, it’s funny because it reveals how addicted we are to the storytelling tropes that comfort us by drawing us away from the mishaps and misunderstandings of our real, everyday lives. Inside a story, everything seems to make so much more sense. We know the rules and rhythms, but as a result we switch off our critical minds and nod along happily to the most blatant nonsense. I don’t think it’s pushing the point too far to think of moments like this as crystallising the essence of the Discworld novels. Pratchett wants us to enjoy the thrills and excesses of a Fantasy tale, but he never allows us to accept them without question.

In a Discworld book, stories are always brought back down to earth. The true king has returned to ‘right all wrongs’? Cue Ankh-Morpork citizens wondering if this means their leaky guttering will finally be fixed. A rampaging dragon might burn the city to the ground? Here’s street-hawker CMOT Dibbler making a quick buck on dubious anti-dragon charms and tacky souvenirs. In Pratchett’s work, the question is always: What would these Big Stories mean in practice, really.

And that’s why it works, why Pratchett was so special. Because he neither dismissed the power and importance of the Big Stories to our lives, nor overlooked the inevitably more complicated and messy ways they’d play out in the lives of real people.8 He had a streak of unusually level-headed romance; a sharply intelligent reverence for the myths that we tell ourselves in order to make sense of the world. He tore down clichés but always recognised that there’s more than a few we should hold on to. Like his friend and collaborator Neil Gaiman, Pratchett teaches us to remember and value our myths, but always to engage them with open eyes and a critical mind.

But he usually takes things a step further, too. He doesn’t simply poke holes in the old stories. Often, he has them come true in much subtler (perhaps realistic) ways. Lupine Wonse and his shadowy brothers spin a hackneyed story about the true king returning to protect and serve the people in their time of need, of a king who’s so pure that he’ll know nothing but the truth and thereby improve the lives of everyone he encounters. This fairytale trope fails for all the right reasons.

And yet here we have Lance-Constable Carrot appearing, as if from nowhere, to join the City Watch. We’re left in no doubt that he really is the rightful king, and although he doesn’t take the throne, Carrot is here to protect and serve the city. He’s deeply moral, and his literal-minded simplicity is a very close neighbour to ‘knowing nothing but the truth’. As The Discworld Companion puts it, Carrot ‘sees the world shorn of all the little lies and prevarications that other people erect in order to sleep at night’.9 Ever so gently, Pratchett manages to take a trope, mercilessly undermine it, and yet still allows the core of the story to play out.

Captain Vimes

Sam Vimes is, quite simply, my favourite Discworld character (I doubt I’m alone in this). And yet, after so many years, re-reading Guards! Guards! was quite a shock: the drunken apathy and despair of the Sam Vimes we find in these pages is a world away from the scything clarity and barely-harnessed moral rage of the Commander Sir Samuel Vimes in later books who lives in my head. Indeed, of all the Discworld sub-series, perhaps the City Watch novels contain the clearest and greatest character development.10

Dragons, politics and puns aside, Guards! Guards! is also the story of a man coming back to life and back to himself. Of a man whose aspirations, moral code, and deepest character have been crushed by a life of disappointment… until something begins to blow a little oxygen onto the tiny ember still burning in his soul.

It would be easy to think of Vimes’s renaissance in fairytale terms: cometh the dragon, cometh the man to defend his home (or something like that). But although this certainly plays a part in Vimes’s rise, the decisive factor is something far simpler: encouragement and kindness.

It’s not something spelled out in the book, but I think the appearance of Carrot and of Lady Sybil Ramkin in Vimes’s life is what makes all the difference. One is a new comrade-in-arms; the other is a nascent love interest. Different as Carrot and Sybil are, they both reshape the world around them through sheer force of personality – not just by bossing people around, but by expecting a better world and better behaviour than really exist.

Vimes is faced with a pair who see a version of himself he thought drowned at the bottom of the bottle. Like most people, when Vimes is treated as if he’s better than he thinks he is, he rises to meet those expectations.

All the same, even after Vimes re-engages with the world and becomes increasingly confident in his sense of what’s right and wrong, he remains deeply suspicious of his own inner world. As we’ll see more vividly in later books, he lives in fear of the darkness that he knows lies within: he struggles every day to be a good man. And that’s what makes him so compelling; not because he’s an anti-hero with a heart of gold, but because he becomes a genuine hero despite carrying a heart of darkness.

Hearts of Darkness

The temptations of evil, or at least of acting so selfishly that you allow evil to happen, are the central theme of this book. The result, it turns out, is the dragon.

Towards the end of the book, Vimes realises something important as he takes a look at the ancient spellbook which the Brethren used to summon the dragon. ‘A realm of fancy, Vimes thought. That’s where they went, then. Into our imaginations. And when we call them back we shape them, like squeezing dough into pastry shapes. Only you don’t get gingerbread men, you get what you are. Your own darkness, given shape…’.11 Lupine Wonse and his Brethren’s dragon was angry, cruel, and thirsty for power. What, then, would Vimes’s dragon have been? In Night Watch, he names that inner darkness ‘the Beast’, desperately trying both to fight and to tame it.

If the great psychologist Carl Jung had lived to read this book, he’d immediately identify this dragon, this ‘Beast’, as Vimes’s shadow – all the darker parts of his personality that he tries to deny, but which are always fighting to burst forth into life. The shadow is all the parts of us that we’ve learnt to hide away, and it’s easy to fear that this might be our true self, hidden behind the persona we’ve learned to play in order to be socially accepted.

Yet in Guards! Guards!, Pratchett gives us another side of Vimes in the form of the small, loveably-goofy swamp dragon called Errol. If dragons, at least in this book, represent parts of the characters’ personalities, then Errol is the better angel of Vimes’s nature. That nature is not at all violent – Errol ultimately puts an end to the big dragon’s reign of terror by showing it love (in probably the most bizarre courting ritual ever recorded). Thankfully, Pratchett was too good a writer to have this play out as a sickly-sweet story of ‘love conquering all’. Nevertheless, it’s still a hopeful story of how small acts of love and kindness can be more effective (and certainly less destructive) than fear and violence.

On the other hand, the two dragons could likewise be telling us a story about Lupine Wonse. He’s the ‘bad guy’ in this novel, but Vimes remembers him from their days growing up as two kids from poor families. Perhaps Wonse – always the smaller boy, trying frantically to make a place for himself among the cooler kids – is the one who desperately needed some love to salve the painful darkness that shaped the violent dragon he summoned.

In any case, Vimes has come a long way by the end of the book. We met him in the gutter, but we leave him beginning a fledgling relationship with Lady Ramkin – a woman who not only helped bring him back to life, but who also happens to be the richest person in the city. That’s no small thing, but the real turning point for Vimes comes a little earlier, when Corporal Nobbs and Sergeant Colon nervously ask the Patrician for a minor pay rise, a new kettle, and a dartboard as their reward for saving the city from a winged killing machine. Vimes bursts into laughter at the sheer incongruity of it all, a laughter that only grows wilder when he sees the confused and affronted faces of the city’s leaders.

It’s a funny scene, but this is no joke for Vimes. For years, the razor-sharp cynicism through which he’s viewed the endless absurdity and petty cruelties of the world has left him depressed, despairing and alcoholic. But now, in this moment, he’s able to laugh rather than to despair – to laugh ‘for the world and the saving of souls’, not least his own. Pratchett was too wise to make this a complete transformation: it’s certainly a turning point, but Vimes laughs ‘until the tears came’. He doesn’t suddenly become a new man, but, like all of us, is working to find his balance on the tightrope between laughter and despair in the face of all the world’s madness and hardships.12

The Banality of Evil

The blurb on the modern paperback claims this book is all about ‘The Haves and Have-Nots’: ‘the Have-Nots have found the key to a dormant, lethal weapon that even they don’t fully understand, and they’re about to unleash a campaign of terror on the city. Time for Captain Vimes to sober up’. It’s a much better pitch than ‘DRAGONS WILL NEVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!’, but, when we take a closer look, it turns out to be just as wrong.

If we take the blurb seriously, then the Elucidated Brethren would be the ‘Have-Nots’, plotting insurrection against the establishment. Except that we have no sense of who the ‘Haves’ are – no doubt the city has its elites, but the spotlight isn’t on them here. Disparities of wealth and class are certainly themes that Pratchett explores in depth elsewhere, but not in this book.

No, this book is fundamentally about two groups of losers: the Brethren and the Watch. Both are downtrodden, ignored, and carry varying degrees of bitterness. They are each in their own way marginalised; the dregs of society. This is a story about how marginalised people may go in two profoundly different directions. The Brethren increasingly give up their personal reservations and allow their moral misgivings to be pushed aside by the promise of power and petty revenge. In contrast, Carrot’s naïve belief in ‘doing the right thing’ shakes his fellow watchmen out of a decades-long, disengaged stupor. In one case, ordinary men are encouraged to give up their critical thoughts and personal responsibility; in the other, men just as ordinary are inspired to question authority and to risk their own safety for the sake of others.

On the surface, this sounds like a classic story of ‘good versus evil’, but in fact it’s a story of how evil always requires our complicity. After the Brethren and the dragon have been defeated, Vimes is summoned to speak with the newly-reinstated Patrician, Lord Vetinari.

While cynical in their own ways, each man’s view of human nature is profoundly different. Vetinari shares a little of his perspective, in order to help Vimes ‘make some sense of the world.’ He continues: ‘I believe you find life such a problem because you think there are the good people and the bad people […] You’re wrong, of course. There are, always and only, the bad people, but some of them are on opposite sides.’ ‘Down there,’ he says, gesturing through the palace window at the sprawling city below, ‘are people who will follow any dragon, worship any god, ignore any iniquity. All out of a kind of humdrum, everyday badness. Not the really high, creative loathsomeness of the great sinners, but a sort of mass-produced darkness of the soul. Sin, you might say, without a trace of originality. They accept evil not because they say yes, but because they don’t say no.’13

And here we are, at the heart of the novel.

The scene doesn’t end here: Vimes protests weakly that people are more often scared than bad; and the preceding pages have shown us that he, at least, will not ‘ignore any iniquity’. Vetinari declares that only ‘evil tyrants’ like himself have the cold, clear-eyed ability to make things work in the long run.14 But while we can decide for ourselves who wins the debate, in the end what matters is that one line: most people accept evil not because they say yes, but because they don’t say no.

These are words that can usefully haunt each of us throughout our lives. This idea is not merely the core of the book, it’s a tenet of Pratchett’s worldview. In his biography, Rob Wilkins tells the story of when Terry, as a young reporter, went to interview Roald Dahl. As Wilkins notes, ‘many of the quotes that Dahl gave to Terry during the interview struck a chord with him that quite clearly continued to resonate’ for decades. One of them was that, although writers should aim to entertain, if there’s any underlying message they can impart, it’s ‘that some people are very nasty and some are very nice. Most people are very nasty, really, when you get down to it.’15

I don’t think Pratchett’s view of humanity was quite so bleak as Dahl’s, but his formative years working for a small, local newspaper certainly left him with a profound awareness of both the toxicity and the ubiquity of small-minded selfishness. These are the traits he brought to petty, bickering life in the members of the Elucidated Brethren. As Lupine Wonse muses to himself, he didn’t choose ‘the skilled, the hopefuls, the ambitious, [or] the self-confident’ to be part of his conspiracy. No, he picked ‘the whining resentful ones, the ones with a bellyful of spite and bile, the ones who knew they could make it big if only they’d been given the chance. Give him the ones in which the floods of venom and vindictiveness were dammed up behind thin walls of ineptitude and lowgrade paranoia’.16

These are not the evil villains of a fairy story; we all know people like this. The self-important colleague who thinks she’s better than everyone else; the deluded friend living in his parents’ basement who thinks he’s always on the cusp of making it big; or merely the insecure administrator who refuses to think outside the box. Their bitterness is so common it’s banal, but it’s no less toxic as a result.17 The Brethren aren’t unrealistic Disney villains; they’re just petty and predictable people. While Lupine Wonse nurtures more complex dreams of using the dragon to seize the throne, his followers fantasise about incinerating nosey neighbours and local shopkeepers who’ve been rude to them.

If Pratchett didn’t think, like Dahl, that ‘most people are very nasty, really,’ he certainly recognised the power of ordinary nastiness to damage society. The ‘Have-Nots’ may not hold swords or high office, but they are far from powerless. When Wonse confronts an unarmed Sam Vimes, he screams: ‘Oh, you think you’re so clever, so in-control, so swave, just because I’ve got a sword and you haven’t!’.18 It’s a funny line because it’s so obviously back-to-front… but it also carries a deeper truth. Pratchett shows us time and again that real, lasting power lies not at the point of a sword, but deep in our hearts and minds. In any society, ordinary citizens will always vastly outnumber the rulers, the soldiers and the watchmen: societies function through barely-conscious consent and shared values. And when that breaks down far enough, you’ve got a revolution on your hands.

That’s why the small, everyday things matter. How we conduct ourselves and how we treat each other. Pratchett not only shows us how small-mindedness and selfishness are easily harnessed and can be disproportionately destructive, he also takes aim at the simple, mundane cowardice that allows terrible things to continue. Once crowned, the dragon demands that the people regularly provide its new king with a high-born maiden to devour. That’s right: a regular human sacrifice. Almost no one speaks up against it: they might not say yes, but they do not say no.

In my work as a historian of twentieth-century Europe, I’ve often had cause to reflect on the disturbing truth of these words. A political theorist called Hannah Arendt coined the phrase ‘the banality of evil’ to explain how quite ordinary people became directly complicit in the Holocaust and the other terrible crimes of the Nazi regime.19 Most were not fanatics, but were simply average, complacent jobsworths who relied on clichés rather than original thought, and were driven, in a deeply prosaic way, more to protect themselves and their future prospects than by any desire to commit evil deeds. No doubt more than a few said yes, but far, far more simply failed to say no. Orthodoxy is ultimately more about silence than agreement.

We see this play out in Guards! Guards! when the Privy Council, composed of the city’s leaders, silently agrees to provide the dragon with its human sacrifice. ‘Each man thought: one of the others is bound to say something soon, some protest, and then I’ll murmur agreement, not actually say anything, I’m not as stupid as that, but definitely murmur very firmly, so that the others will be in no doubt that I thoroughly disapprove, because at a time like this it behooves all decent men to nearly stand up and be almost heard… // But no-one said anything. The cowards, each man thought.’20

Yes, this is all about a dragon, but beneath the fantasy trappings sits a darkly human truth: once you’ve saved your own backside by doing what you’re told, it’s dangerously, seductively easy to look the other way while bad things happen to other people.

And it’s not just the powerful who’re faced with this choice. The Privy Council scene is grimly cynical, but seeing the same behaviour from more ordinary people hits much closer to home. Even Sergeant Fred Colon, one of the obvious ‘good guys’ in this story, clings to the idea that ‘people’ – meaning other people – won’t stand for this. And when he does try to make a stand (with the wonderful slogan that ‘the people united will never be ignited!’), the dragon’s arrival soon has him trying desperately to melt back into the silent crowd. The big question we have to ask ourselves is: would we do any different?

Lupine Wonse and his little cabal are obviously culpable for summoning the dragon, but are they really much worse than anyone else? They didn’t intend to kill anyone, but once the dragon rips itself free of their control, its murderous reign of terror is not met with armed resistance, but with quiet grumbling and tacit acceptance.

One of humanity’s greatest strengths is our adaptability. Yet it can simultaneously be our greatest weakness. As the city’s new ruler, the dragon assumes there’s a simple equation underlying its power: people will do as it says, or it will kill them. But Lupine Wonse explains that, in fact, fear won’t be necessary in the long run. ‘We humans are adaptable creatures,’ he says; soon enough the citizens will think that a regular human sacrifice to a dragon king is completely normal. As various psychological studies suggest, we’re so wired to think of ourselves as ‘good, decent people,’ that we’ll find an endless supply of justifications for the bad things we do. ‘I’m a good person,’ we think, ‘so if I’m doing this, then it must be the kind of thing a good person would do’. And so, Wonse tells the dragon, ‘before too long, if someone comes along and tells them that a dragon king is a bad idea, they’ll kill him themselves’.21 It’s a horrifying thought, not because it’s ridiculous, but precisely because it’s so plausible.

Ankh-Morpork’s fickle, gawping crowds provide plenty of comic relief, but the uncomfortable truth is that most of us are just like them. Few of us could be a Sam Vimes, but it’s reading and imagining characters like him that can help us to reach a little higher than we otherwise might. Just as Carrot inspires Vimes and the other watchmen to choose Right over Safe, throughout the series it’s Vimes’s struggle to be a good man which I find most compelling. To be willing to stand up and say no in the face of corruption, abuse, or arbitrary violence – not just when it feels safe to do so, but especially when it is not.

Still, Pratchett doesn’t lie to us or sugar-coat it: the one man (a father of three daughters) who openly defies the dragon to its scaly face is immediately burnt to a crisp.22 Doing the Right Thing is worth a lot; it could cost you everything. In Terry Pratchett’s world, that may be a price worth paying.

And yes, like every other player, 20 years later we’re still apt to fly into a mixture of rage and frustration whenever we hear the phrase ‘That doesn’t work’.

Guards! Guards!, p.114. All references are to the 2012 paperback edition.

There’s even a backhanded comment in Pyramids about how irrelevant the Watch is compared to the Guilds. This was the novel immediately preceding Guards! Guards!, so perhaps that little comment became a seed for what Pratchett decided to do next.

GG, p.106.

GG, p.115.

Rob Wilkins, Terry Pratchett: A Life with Footnotes (London, 2022), p.107.

GG, pp.15-18.

This is something it took historians generations to appreciate. Only in the past fifty years or so has it become common to look at history ‘from below’ – focusing not on monarchs, big men, or decrees from on-high, but instead on what those decrees actually meant to ordinary people. Today, most historians wouldn’t just assume that regular folk were filled with patriotic fervour just because they turned out en masse for an official celebration. Because they could just as well be motivated by, say, the chance to have a day off work, enjoy a party atmosphere, and (most important of all) the chance to consume as much free food and drink as possible.

Terry Pratchett & Stephen Briggs, The Ultimate Discworld Companion (London, 2021), p.62.

By contrast, however different the plot and the setting, are major recurring characters like Rincewind or Granny Weatherwax markedly different from book to book? Perhaps I’ll have cause to eat my words when I come to re-read those books, but I don’t think so.

GG, p.408.

GG, p.414.

GG, pp.405-6.

Vimes and Vetinari’s relationship is one we’ll be coming back to many times over the series. Their face-offs towards the end of most City Watch novels usually draw key threads of the story together. And in time we’ll see how – despite their very different perspectives on humanity, power, and morality – the two men are deeply connected and ultimately come to rely on each other.

Wilkins, Terry Pratchett, p.130.

GG, p.20.

The most damning detail about the Brethren’s selfishness – at least to a British audience – is that they always leave their rented meeting room in a terrible mess and never clean out the tea urn.

GG, p.398. Spelling original.

Arendt was specifically discussing Adolf Eichmann – whom she perceived as a thoroughly banal, mediocre individual – but the concept is now applied far beyond this single case.

GG, pp.302-3.

GG, p.306.

GG, pp.321-4.